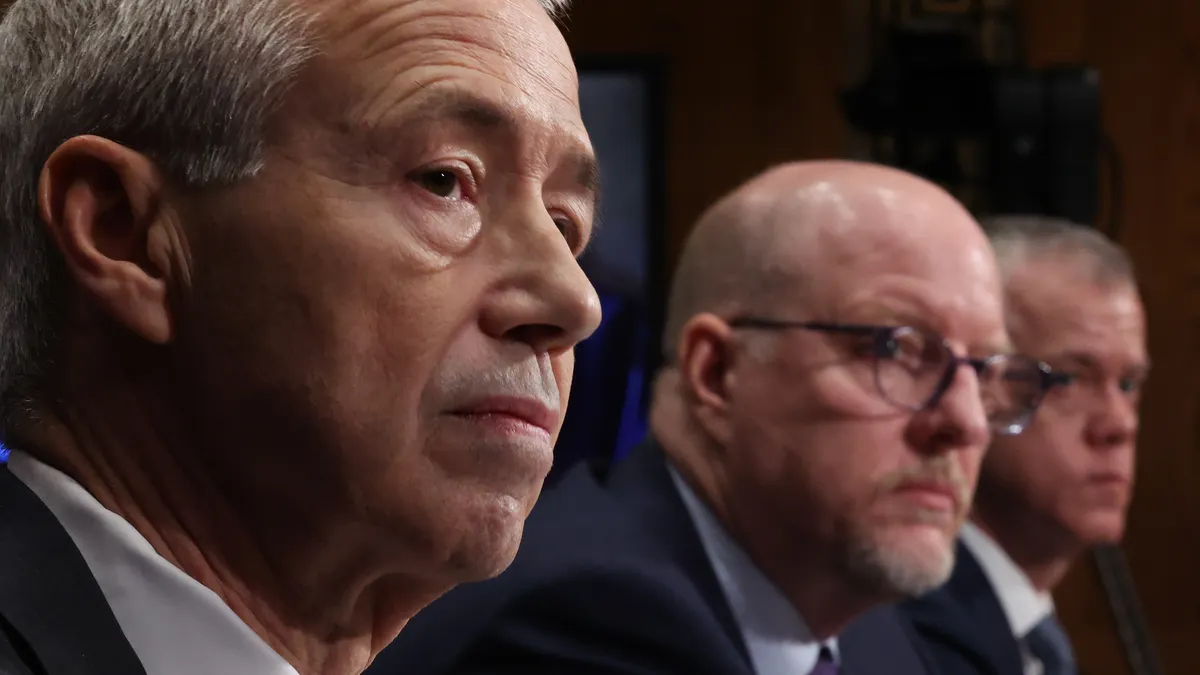

Dr. Patrizia Cavazzoni. Dr. Jacqueline Corrigan-Curay. Dr. George Tidmarsh. Dr. Richard Pazdur. Dr. Tracy Beth Høeg.

These five doctors have one major thing in common: They have all been director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research this year, reflecting a tumultuous time at the U.S. regulatory agency in charge of ensuring drugs are safe and effective.

Turnover in the highest ranks of the FDA and other health agencies has contributed to a sense of uncertainty that could disrupt regulatory decision-making and strategic planning, said Paul Perreault, former CEO of Australian drugmaker CSL.

“From the commissioner on down, people have been moving in and out, and it’s potentially been causing instability within the FDA,” Perreault said.

Amid the disruption, however, these institutions are too big and complex to be swayed so easily in the near-term.

“A lot of what happens at the FDA is below those top levels, and in terms of what happens in the bowels of the department, it’s hard to change,” Perreault said. “The FDA still has the highest bar for regulations in the world for drugs and drug approvals, and the people who work in those departments and actually go through all the documentation are getting it done.”

Still, despite the consistent flow of the agency’s undercurrent, the revolving door at the top of departments like CDER, as well as the communication that circles these changes, instability threatens to change the fabric of the institutions as changes in leadership make oversight a challenge.

For example, the involvement of HHS in affairs at lower agencies like the FDA and the CDC is unlike any previous administration Perreault has seen. But while rhetoric from the top trickles down through the agencies, it also takes time to change the direction of a ship the size of the FDA.

“The biggest thing in the news right now is vaccines, and you can talk to 1,000 people and get 1,000 different opinions on the matter, but the policies haven’t changed in terms of what you need to do to get over the hurdles for approval,” said Perreault, who led the vaccine maker CSL through the COVID-19 pandemic.

‘Institutional memory’

At CSL, Perreault worked with the FDA as part of Operation Warp Speed to develop a hyperimmune globulin product for COVID-19. While the program conveyed “mixed results,” Perreault said the cooperation with the FDA was organized and efficient.

Now, amid the exodus of experienced leaders, the story might be different, he said, and come down to the agencies’ supply of “institutional memory,” which maintains the complex system through consistent direction. But that institutional memory is threatened with the loss of about 20% of CDER employees since January.

“What institutional memory brings is a good understanding of how the system can work, and if you haven’t worked within that system, it’s complicated,” Perreault said. “It’s a massive organization with a massive process, and at the top levels of these agencies and committees, you have to understand the process.”

In theory, institutional memory could mire health agencies in older ways of operating. But Perreault sees it differently. Consistent leadership allows for adaptability by knowing which levers to pull, and when to speed up or slow down.

“You can’t just accelerate everything on day one, or it will be chaos — it’s a matter of setting the strategy, which takes time, and getting things moving reliably,” Perreault said. “Good leaders can draw from institutional memory and understand the process while they’re pushing forward for change.”

Alongside high-profile changes to vaccine guidelines, leaders have pulled the FDA in different directions over the course of the year, promoting ultra-rare disease treatments, giving U.S. manufacturers a push and opening up the complete response letter process to the public.

For drugmakers in the throes of R&D, Perreault recommends looking past the turbulence and playing the long game.

“R&D is a long process, seven to 10 years from the time you start, and everything that happens with the agency is near-term,” Perreault said. “What drugmakers should be focused on is getting clarity and trying to understand where regulation is heading — the majority of the FDA is not going to change that much.”

Pharma companies heading into regulatory discussions need to keep their finger on the pulse of what changes are coming down the pike — like new vaccine guidelines — but realize that many aspects will remain the same.

“There will still be hurdles to get over, and you just need to know whether it’s a three-foot hurdle, four-foot hurdle or a six-foot hurdle,” Perreault said.

Rebuilding trust

With leadership changing so frequently, it can be difficult for drugmakers to understand what regulators want. And within the agencies, it can be difficult for employees to understand what their bosses want, as well.

This erodes trust that needs to be rebuilt, Perreault said.

“That’s not the way you operate any organization,” he said. “Hiring is hard because you’re dealing with people, politics and personalities, but you also need consistency in leadership if you’re going to build trust.”

Perreault thinks the storm will subside, and that the institutional memory that remains will fuel the FDA and other health agencies for the longer term.

“In the next couple years, things will settle down, and the agency will continue on,” Perreault said. “There are a lot of people still doing great work and managing the process underneath all of this upper level movement, and I feel comforted by that.”