Big Pharma has long been synonymous with money and influence in healthcare. Now, the massive global wellness industry, which is nearly four times larger than the $1.8 trillion pharmaceutical sector, is gaining influence within federal health agencies and raising questions about potential conflicts of interest.

Consumer spending on wellness-related products, which range from supplements to fitness equipment and spa services, brought in $6.8 trillion in 2024, according to the Global Wellness Institute. And because of the industry’s connections to several high-profile regulatory leaders, its proximity to Washington is expanding, even though its political spending remains modest. Wellness lobbyists spent only about $3.7 million in 2024 — a far cry from pharma’s $387 million tally.

Even so, industry ties with Health and Human Services leaders are drawing scrutiny from congressional leaders and healthcare experts pushing for more transparency and safeguards to prevent unfair influence on federal policy.

Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Andy Kim (D-N.J.) sounded the alarm in October about the nomination of surgeon general candidate Dr. Casey Means, who has a medical degree but no current license, and lucrative financial ties to a number of wellness companies.

“Over the course of her career as an influencer, Dr. Means has received hundreds of thousands of dollars to promote a variety of wellness products and invested in numerous wellness companies,” the senators stated in a joint press release.

Means founded a company that sells glucose monitoring devices for people who aren’t diabetic and has called for public policy that encourages healthy people to monitor their blood sugar, despite no evidence of a potential benefit, according to KFF.

Her confirmation hearing, set for Oct. 30, 2025 was delayed when she went into labor with her first child, and has yet to be rescheduled.

These potential conflicts carry the same risk of influencing policy as ties to the pharma industry, long criticized by those within the Make America Healthy Again movement. Officials at HHS, however, have pushed back on criticism related to wellness, saying they comply with ethics and financial disclosure laws, according to KFF.

The two Means

Casey Means isn’t the only wellness-linked leader whose HHS ties have generated concern. Officials also raised questions during the tenure of her brother, Calley Means, a former lobbyist and entrepreneur, while he served as an informal advisor to HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Calley Means co-founded a wellness company, Truemed, which sells a wide range of products, including supplements and health tech devices. Unlike government employees, informal advisors aren’t required to divest from companies that present a potential conflict or publicly disclose their financial ties.

Congressman Jake Auchincloss (D-Mass.) and Senator Adam Schiff (D-Calif.) sent a letter demanding more transparency about potential conflicts of interest before Calley Means reportedly left his government position in October.

Another informal Kennedy advisor, Dr. Peter McCullough, a cardiologist and vaccine skeptic, also faced criticism for allegedly profiting from his anti-COVID-19 messaging through his role as chief scientific officer at The Wellness Company, according to KFF. Its offerings include a supplement based on his protocol to “detox” from the COVID infections or vaccines, claims that public health experts say are not supported by scientific evidence.

Vaccine concerns come true

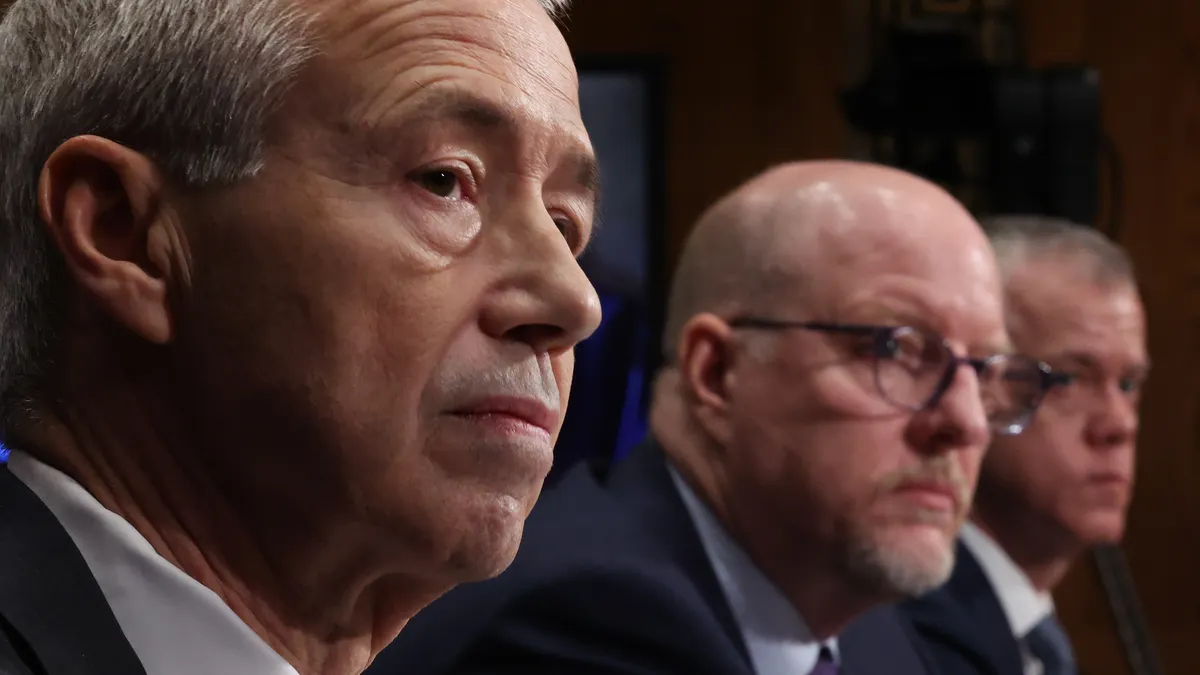

Other members of the MAHA movement remain connected with anti-vaccine interests. Kennedy drew fire at his confirmation hearing over concerns that he earns referral fees from a personal injury law firm where his adult son works, for linking the practice with patients who say they’ve experienced a vaccine-related injury.

He also stood to profit from lawsuits against Merck & Co.’s Gardasil HPV vaccine. While Kennedy later agreed to amend his ethics agreement, Warren issued a statement that said the modification didn’t eliminate her concerns.

Kennedy also raised eyebrows last year when he removed all 17 members of the CDC’s vaccine advisory committee, installing replacements that included vaccine skeptics. While Kennedy said the decision was made to reduce conflicts of interest on the board and to restore public trust, one analysis determined that conflicts were at a historic low at the time of the change.

Some of the new members also brought their own conflicts, including Dr. Robert Malone, an infectious disease researcher known for his anti-vaccine views. Warren blasted the board reorganization.

“As presently constituted, the committee lacks the qualifications and credibility to offer the nation credible advice on vaccines,” she said in a press release. “You have promised that, as HHS Secretary, you would root out conflicts of interest and promote ‘radical transparency,’ but you are failing miserably to meet this promise as you rush to impose your anti-vaccine agenda on the American public.”

True to those concerns, the new vaccine committee has since levied several controversial recommendations.

In December, the committee weakened hepatitis B vaccine recommendations, raising alarm bells among medical groups that said the change ran counter to scientific evidence. It also recently announced a highly controversial reduction in recommended childhood vaccines based on an assessment written by Martin Kulldorff, a chief science officer at HHS, and another of Kennedy’s controversial appointees, Dr. Tracy Beth Høeg, a sports medicine specialist and vaccine skeptic who’s now acting director of CDER (the fifth director appointed to the post in the last year).

Her appointment unnerved some FDA officials and public health experts. Although Høeg doesn’t appear to have financial ties that present a conflict, her lack of experience and controversial views on vaccines have raised fears she will politicize the office.

And while the pharma industry is heavily regulated and monitored, the wellness world has fewer guardrails. Congressional critics say transparency and safeguards should be universal.

“Just as we need ethics guardrails to prevent Big Pharma companies from using insider connections to exert undue influence on policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, so too should ethical guardrails apply to all conflicts of interest,” Warren and Kim wrote.