Last week, the Trump administration and Pfizer announced what the drugmaker called a “landmark agreement to lower drug costs.” Now that the dust has settled and the terms of the deal are coming into focus, many experts agree on three points.

First, the Trump administration secured a political win. Second, Pfizer made limited concessions while avoiding a potential tariff hit. And third, some of the deal’s main components, including TrumpRX, a direct-to-consumer sales website, and the “most favored nation” (MFN) pricing for Medicaid patients may only meaningfully reduce drug prices for a narrow group of patients.

What’s less clear is how a push to get Pfizer and other drugmakers to align U.S. drug prices with what other nations pay will play out.

Under the deal announced at the end of September, Pfizer agreed to price newly launched medicines in line with developed markets and to ”repatriate” increased revenues generated by these trade policies to the U.S., although the company hasn’t explained how this will be accomplished.

“By other countries paying more, it's going to help the U.S. not have to pay as much because the cost is going to be spread more evenly among the high-income countries.”

Jeffrey Gerrish

Attorney, former U.S. deputy trade representative

And while the Trump administration often touts its efforts to lower prices in the U.S. by matching what other countries pay, there’s more to this policy story. Part of the MFN strategy could also involve making other countries pay more — bringing the end prices to a negotiated middle ground and perhaps not lowering them as much for consumers overall.

“There's still a lot we don't know about the specifics of the Pfizer deal. However, I think they will move toward raising prices abroad, similar to recent announcements by AbbVie and Bristol Myers Squibb,” said Jeffrey Gerrish, an attorney who served as deputy U.S. deputy trade representative for Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and industrial competitiveness during the first Trump administration.

AbbVie and BMS recently announced that their drugs, Elahere for ovarian cancer and Cobenfy for schizophrenia, respectively, would enter the U.K. market at American list prices, marking a significant shift in traditional pricing policies.

The terms of the Pfizer agreement reflect demands issued to drugmakers in letters earlier this summer in which the Trump administration framed the pricing initiative as a means to end “global freeloading on American pharmaceutical innovation.” The administration has railed against what it deems an unfair burden Americans bear from higher drug prices.

Many branded drugs for conditions like diabetes or cystic fibrosis cost significantly more in the U.S. than in other nations, said Sandy Donaldson, co-founder and president of Impiricus, and a former UCB executive. For example, Humira cost 423% more in the U.S. than in the U.K. and 186% more than in Germany, according to Peterson-KFF analysis in 2022.

Countries with national healthcare systems often negotiate drug prices or cap costs. If drug companies bring U.S. prices in line with other countries, affordability for Americans could improve, Gerrish said.

If companies agree to introduce new medications in the U.S. at prices that match the lowest price offered in developed nations, it would provide an incentive to ensure those prices aren’t “artificially low,” he said. If the price is too low, companies might opt not to introduce the drug in that market. That country, fearing lost drug access, has an incentive to negotiate.

“By other countries paying more, it's going to help the U.S. not have to pay as much because the cost is going to be spread more evenly among the high-income countries,” Gerrish said.

The initiative could offer a fair way to rebalance the global pricing system. However, if the predicted effect materializes, it could take time.

“Not all of these drug companies are going to suddenly jack up the prices tomorrow in Europe,” Donaldson said. “I think within a year's time from now, you will see some rebalancing of prices globally.”

Experts split on likely outcomes

Not all experts agree that applying pricing pressure abroad will succeed, and the decision by AbbVie and BMS to bring U.S. prices to the U.K. has already generated pushback.

Organizations such as Balanced Economy Project, Just Treatment and Global Justice Now, have called on the U.K.’s Competition and Markets Authority to investigate what they call “anti-competitive conduct” by major pharmaceutical companies and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. The groups accused AstraZeneca, Merck & Co. and Eli Lilly of a coordinated effort to drive up the cost of medicines in the U.K. amid the Trump administration’s demands.

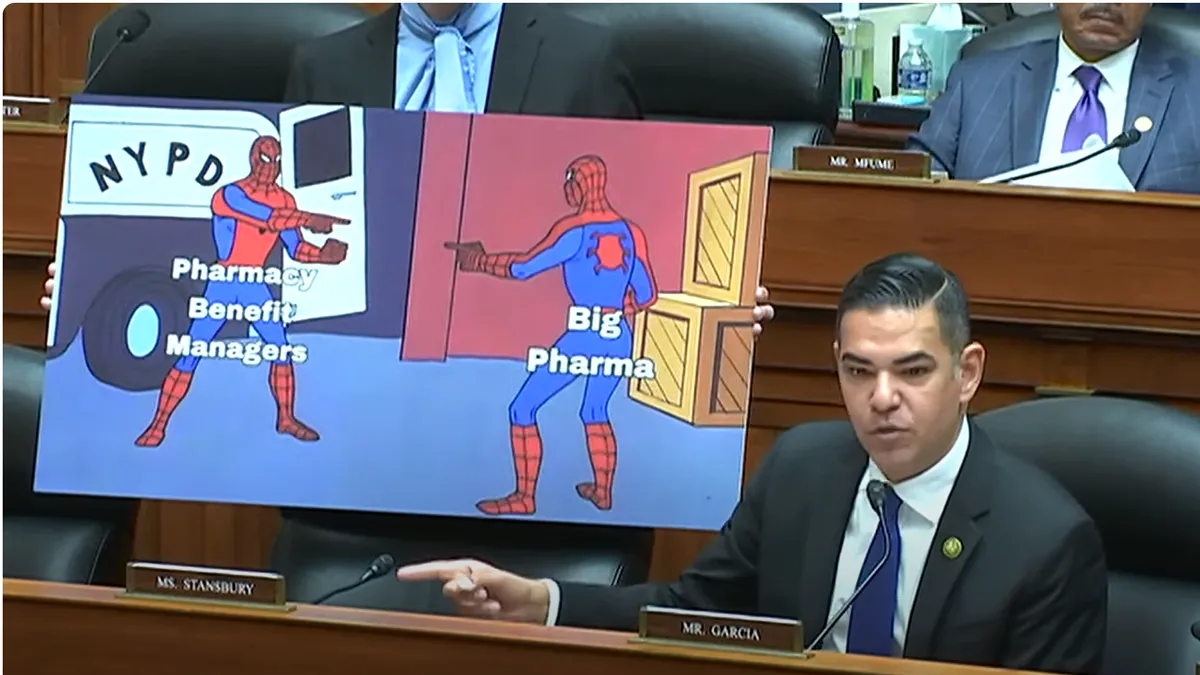

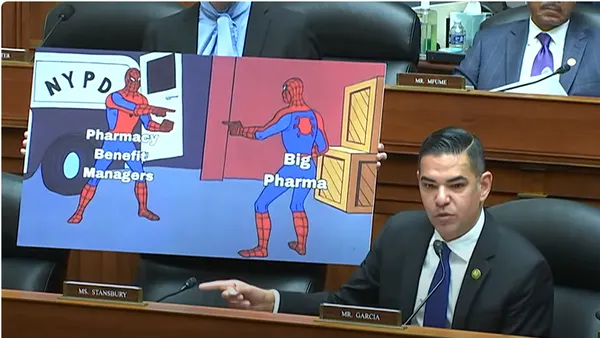

Some experts are also not convinced that the MFN pricing policy will draw a straight line to lower prices.

“The U.S. government’s reliance on the most favored nation pricing model — tying drug costs to the lowest price paid by other countries — is a politically appealing but structurally flawed solution,” said Ganeswar Matcha in an article published by Harvard Law School’s Petrie Flom Center, pointing out that the policy could spark trade disputes, legal challenges, and raise economic and ethical issues. “MFN pricing does little to fix the structural drivers of inflated drug costs in the U.S. — most notably, patent system abuse.”

MFN pricing policies may also have an outsized impact on smaller companies with limited product lines, according to a memorandum from Skadden law firm.

And critics warn that reduced revenues triggered by the initiative could stifle innovation.

“There will be downstream changes to R&D, to pipelines, and in the long term, there will be impacts on the innovative medicines that are being developed,” Donaldson said.

Will others follow Pfizer?

While it remains to be seen if other large pharma companies will follow Pfizer’s lead, some have indicated they’re in talks with the Trump administration about making a pricing deal. And it does appear Pfizer positioned itself well by being the first to negotiate.

The deal spared the company from a threatened 100% tariff Trump vowed to impose Oct. 1, though reporting indicated the tariff hasn’t gone into effect and officials have not offered a new timeline.

Still, Gerrish predicts other companies will fall in line.

“It will make sense for them because otherwise, the administration could take action that could put them at a competitive disadvantage in the marketplace,” he said.